We would like to go a bit deeper and share OUR economics in this model…

An annual income of a few thousand dollars goes far in a country with a median income in the hundreds, and we know how to achieve that greater income with Direct Access.

With our Direct Access model, we are able to control and establish many of the supply chain economics upfront.

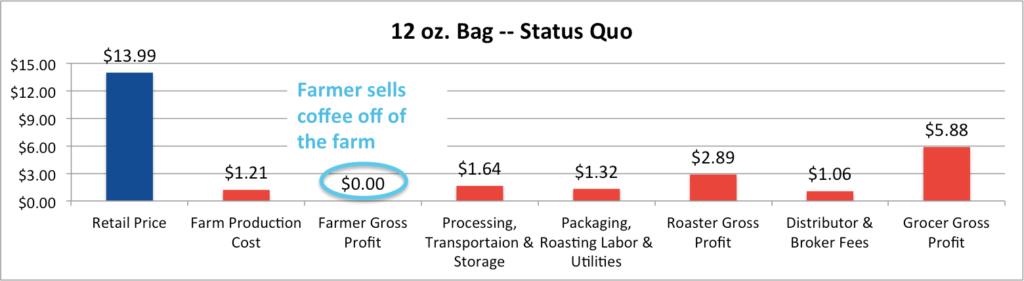

If you happen to have even the smallest social justice vein running through your body, I would ask you to sit down, stay calm (deep breaths), and keep an open mind. You will be tempted to read the next chart and pointedly ask, “Why does so-and-so make so much, when the farmer gets so little?” In broad strokes, this is THE problem we are tackling: we are looking for a new way to approach the coffee supply chain to create efficiencies and eliminate gross disparities, shifting profits more in favor of the farmer.

Here is what the money flow looks like for a typical finished 12-ounce bag of specialty coffee at your grocery store:

The above chart is based upon a number of assumptions:

-production cost of $1.35/lb of coffee to the farmer (an average across seven Latin American countries based on data presented by Caravela Coffee in their 2019 white paper underpinned by extensive on-the-ground work, https://caravela.coffee/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/COP-White-Paper-July-2019-FINAL.pdf)

-$1.35 per lb farm gate price paid to the farmer (a great price versus the low commodity market at present (August 2020)–the farmer is actually doing much better in this example than if they sold on the commodity market.

-fairly typical processing and import expenses

-8% distributor fee

-5% grocery broker fee

-42% grocer margin

You might ask if this is possible. Are these economics reasonable or common? After all, the farmer is merely breaking even. Not only is this quite possible, this can be almost typical in some countries. In 2018, 53% of the smallholder specialty coffee growers in Colombia lost money on their crops according to the Specialty Coffee Association, based on a collaborative study from University of Muenster’s TRANSSUSTAIN research project, University of California Davis, and the International Coffee Organization, https://sca.coffee/sca-news/25-magazine/issue-11/the-cost-conundrum

So now, why do all of those other people get so much money, when the farmer is getting so little? There are in fact some good reasons in many cases. Even with domestic products with relatively little processing, the farmer often receives a very small percentage of the final retail price. In coffee’s case, there are a large number of necessary, value added steps that must occur between a coffee cherry being picked and your purchase of a roasted bean in some locale thousands of miles removed from the farm. There are a lot of hands that must touch your coffee on that journey, and all of them are looking to get paid.

There in fact, are not a lot of people getting filthy rich in the specialty coffee trade–those who are, are outliers. In real dollars, grocery stores make the most off of each bag of coffee sold as you can see above. Factor in the overhead that the grocery store faces, however, and the grocer may be among the least profitable members of the supply chain. An international shipper who makes only pennies off of each bag that ultimately sells on a grocery shelf is moving huge volumes, may have the least risk in their business model, and the owners might be doing Scrooge McDuck dives into piles of cash. The roaster… yep, the roaster typically receives a lot of the overall take from the sale of a 12-ounce bag, but for most specialty roasters (ourselves included) equipment, labor, and marketing costs are significant, and these costs are incurred in an expensive, developed economy.

A family will starve on a few thousand dollars of income in a year in the United States, yet in many coffee growing countries the median annual income is in the hundreds of dollars, not thousands. There are vast disparities between the local economies and normal or accepted “standards of living” between supply chain actors at the beginning and end of the supply chain. These factures should not be an excuse to avoid taking action, but they should be recognized when we look at the supply chain and try to determine what is equitable (or even reasonably achievable) for all parties. While the determination of what is equitable might be subjective, barely breaking even or straight out losing money is unsustainable for all. Smallholder farmers are among the most vulnerable of all the supply chain actors when they do find themselves unprofitable. At present, there are significant numbers of smallholder coffee farmers who are losing money on their crops and only surviving by tapping into additional “free” family labor or supplementing with other crops.

We are confident that there is a model that allows all supply chain actors to make a more predictably sustainable income, and importantly, provides more income and long-term sustainability for smallholder farmers.